In the Digital Microcosm, Leah Miller '14 scanned and annotated striking pages from the College's yearbook between 1868 and 2013. Readers can skip to particular eras using the table of contents on the first page. To see Miller's remarks and annotations, click the red plus sign at the bottom right hand corner of each page. Your thoughts and comments are very welcome below.

REFLECTION ESSAY

A Senior Independent Study

By Leah Miller

Introduction

I began this project during the last semester of my senior year as part of an independent study on Digital History. The purpose of the Independent Study was to become involved with the Dickinsonia project, a team of History Department faculty and students committed to presenting a richer history of Dickinson for the new college website. While at first I presented on various timeline software and assisted more in the macro capacity, I quickly became involved in my own project to present a history of Dickinson’s Student Life in the form of a digital yearbook. But rather than including all of the many events we would discover throughout the semester, I limited myself to only what was in the Microcosm, Dickinson’s own yearbook. The result is a microcosm of the Microcosm, itself a microcosm of the greater world. Through hundreds of hours researching, scanning, annotating, and assembling, I came to know the history of my college—the delightful, the admirable, and the abhorrent. And I can honestly say, after all that, I’m honored to call Dickinson my college.

History of the Microcosm

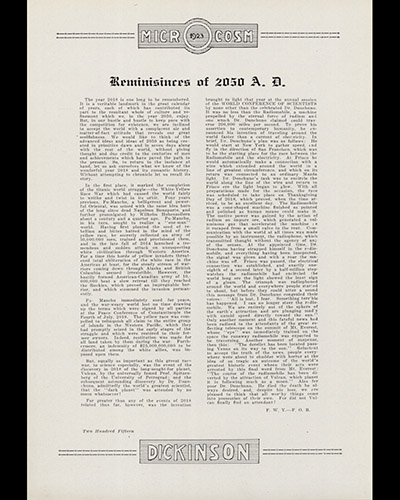

Dickinson College’s Microcosm was first published by the senior class in 1868, and continued sporadically for a few years before becoming a regular publication after 1890. The first editions contained a few oddities, most notably the Microcosm of the class of 1870, which that class published as alumni over thirty years later in 1903, and the Minutals of 1881 and 1882, which the Phi Beta Kappa fraternity published in an attempt to jumpstart regular publication of the sparse class books. Moreover, as a result of inter-fraternity competition, the year 1882 saw two yearbooks at Dickinson, the Minutal and the revived Microcosm—though the next publication wouldn’t be until 1890. There are more than 145 years of Dickinson’s history contained within the pages of the Microcosm, which I say because many editions provide their own interpretation of past events at the college, from its founding days with Charles Nisbet and Benjamin Rush to glimpses of college leadership during the Civil War. In 1923, two authors even wrote “Reminiscences of 2050 A.D.,” a piece which fictitiously remembered the events of 2018, when the “race war” between the Chinese and North Americans ended, and the great scientist, Dr. Donchuno, lost control of his radiomobile and plummeted out into space. The yearbook is also a microcosm of the greater world—politically, aesthetically, and historically—and I needed to decide how to fill the pages of my own microcosm.

Dickinson College’s Microcosm was first published by the senior class in 1868, and continued sporadically for a few years before becoming a regular publication after 1890. The first editions contained a few oddities, most notably the Microcosm of the class of 1870, which that class published as alumni over thirty years later in 1903, and the Minutals of 1881 and 1882, which the Phi Beta Kappa fraternity published in an attempt to jumpstart regular publication of the sparse class books. Moreover, as a result of inter-fraternity competition, the year 1882 saw two yearbooks at Dickinson, the Minutal and the revived Microcosm—though the next publication wouldn’t be until 1890. There are more than 145 years of Dickinson’s history contained within the pages of the Microcosm, which I say because many editions provide their own interpretation of past events at the college, from its founding days with Charles Nisbet and Benjamin Rush to glimpses of college leadership during the Civil War. In 1923, two authors even wrote “Reminiscences of 2050 A.D.,” a piece which fictitiously remembered the events of 2018, when the “race war” between the Chinese and North Americans ended, and the great scientist, Dr. Donchuno, lost control of his radiomobile and plummeted out into space. The yearbook is also a microcosm of the greater world—politically, aesthetically, and historically—and I needed to decide how to fill the pages of my own microcosm.

Methods

From a span of tens of thousands of pages, I chose only 384 to fill my history, but what I chose was restricted twofold by the choices of former Dickinsoinians. The final product you are viewing is only a sidelong glance at What Happened, which has been filtered repeatedly through the lenses of interpretation: someone chose the pictures to take and the words to write, the editors chose which of these to include in the pages of each yearbook, and I chose which pages to include in my history. As such there are certainly important events missing from this history: Martin Luther King’s visit to campus in 1961 stands out to me as one of the most noticeable in its absence.

Whereas most historians would work chronologically from the beginning, I began by selecting pages from the most recent editions of the Microcosm, and worked backwards from there. It would be only later that I’d realize I did this because I was most comfortable with the present—I knew what was important in my time at Dickinson: huge charity events for Japan and Haiti, the construction of the Althouse Trellis, Bill Ayers’ controversial visit (missing was the 2012 Old West Sit-In to protest against our sexual violence policies).

As I began to move backwards in time, my study began to be more about connections: origins or precursors of events I knew were relevant today, occurrences that linked to greater events in the world outside Dickinson, tracing stories I found back to their beginnings. That’s how I found the Dickinson-in-China program that started in 1910; it wasn’t a study abroad program like we have today, but Dickinson faculty and alumni missionized in the Szechuan Province and brought back stories and lectures for Dickinson students. It’s why I looked for hints of war in the 1930s and discovered that a rabbi came to campus in 1934 to talk about German atrocities against Jews, and that German exchange students were equipped with high-quality cameras and were leaders “of high rank” in Hitler’s Youth. It’s the reason I paid special attention to the treatment of women and of people of color, and chose specific images to show how they were represented and how they came to represent themselves.

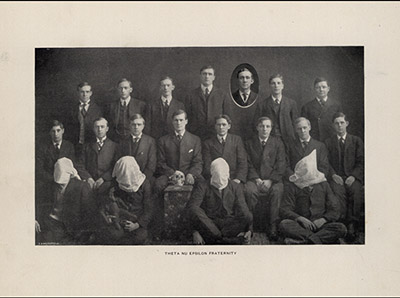

Sometimes I chose pages because at first they seemed ridiculous. A 1906 photograph of the eerie Theta Nu Epsilon fraternity caught my eye because it’s absolutely terrifying. I was lucky (I call it lucky because I’d be so excited about the things I had found that I’d talk about them to people I knew on campus—in this case, Dan Confer ’02) in finding out later that they evolved into the Society of the Skull and Key, or Black Hats, which was disbanded by the faculty in 1983 for inordinate hazing. The society was reinvented in 2001 as the Society of the Scroll and Key, an organization dedicated to community service and academic excellence.

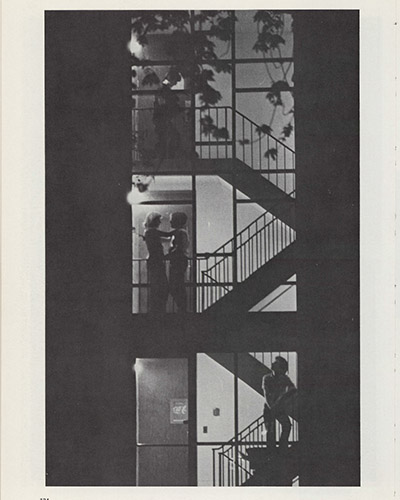

And I pulled out quite a few pages because they were simply beautiful. My favorite is a photograph from 1978: a couple stands ready to kiss in the second floor stairwell of a quads building, while a student on the first set of stairs looks around as if he’s just heard them, and a student with arms full of books descends from the third floor. It’s nighttime, and all this is silhouetted in perfect geometry. It speaks so perfectly to students, then and now: some things change, like fashion and technology, but the spirit—of dorm life, and young romances—that stays the same. And the building is still there; that stairwell is unchanged.

Though this project is in no way comprehensive (and it could never be complete), I tried to represent everybody in some capacity, and with certain subjects I had to ask for help. Director of Athletics Les Poolman showed me our best moments in sports history, and Professor Emeritus John Osborne, who’d taught at Dickinson since the 1970s, told me the best stories and gave me some great leads. Professor Todd Wronski helped me find the most significant moments in Dickinson’s theater history: the first play in Mather’s Theater, Stuart Pankin’s costume in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, and one thing that didn’t show up in the Microcosm, but I have to mention it anyway—theater student and later full-time tech director of the Mermaid Players, Jim Drake, who painted a flag in his own blood to protest the Kent State shootings. I even involved my best friend and fellow student, Aaron Brumbaugh (’14), to help me with the science side of things—leading to his excited discovery that Carl Sagan came to campus to receive the Priestley Award in 1975.

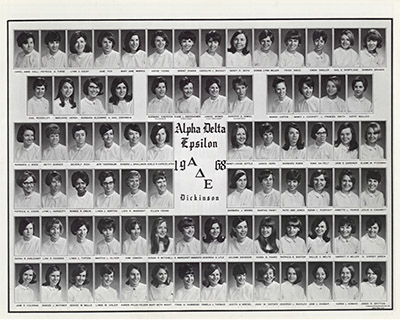

And some of my greatest help came from Dickinson alumni, most notably Karen Pflug-Felder (’71), who helped me make sense of the Seventies, that beautiful collection of photographs without captions, mostly of children, people kissing, and multiple frames of students making strange faces. It was through her that I found the story of Bobbie Swain (’70), the African American woman whose sorority cut ties with its national organization in order to admit her as one of them.

And some of my greatest help came from Dickinson alumni, most notably Karen Pflug-Felder (’71), who helped me make sense of the Seventies, that beautiful collection of photographs without captions, mostly of children, people kissing, and multiple frames of students making strange faces. It was through her that I found the story of Bobbie Swain (’70), the African American woman whose sorority cut ties with its national organization in order to admit her as one of them.

Finally, I have to admit a glaring error. It wasn’t until I had scanned and assembled everything into an electronic document that I tallied the number of pages from each decade. While on the whole, the project is fairly evenly distributed, I spent hardly any time on the 1950s and 1980s (not coincidentally the most conservative decades) and by far the most pages come from the 1970s, undoubtedly because I found it to be the most fascinating decade—politically, aesthetically, culturally. For this I apologize to readers from the ’50s and ’80s, or anyone interested in those decades. At some point in the hundreds of hours I spent researching, scanning, and assembling pages, this project absorbed a bit of me—and I of it—and it might have a totally different feel if someone else had compiled it.

Possible Interpretations

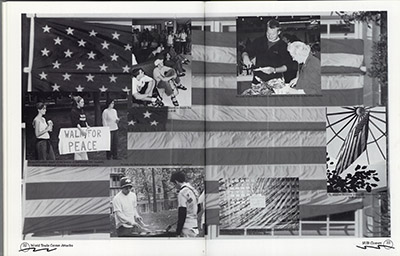

There are plenty of ways to read this online book. First, you could look at it as I did the originals, as a historian trying to piece together from the evidence one main narrative full of incongruities and questions. You could analyze publication techniques: how fonts grew and diminished in popularity, how page-layout worked, how photography itself changed (regrettably, I didn’t think to pinpoint the year of the first color photograph in the Microcosm until it was too late). Or you could choose a theme like Student Protests at Dickinson, piecing together a story involving tense student-faculty relations, marches on the U.S. Army War College, the J. P. Stevens Textile Company, and a guillotine erected in the quads. Just one page alone can tell you so much. Take, for instance, the two-page spread dedicated to the September 11th attacks: at first I wondered why there were so few pictures, until I considered that every student’s eyes were glued to the television screen. And every picture was so carefully chosen, showing all sides of the tragedy as it occurred at Dickinson. Even the background image is not merely filler, but rather a photograph of the enormous flag erected by library workers along High Street. The depth of emotion in these pages is moving.

There are plenty of ways to read this online book. First, you could look at it as I did the originals, as a historian trying to piece together from the evidence one main narrative full of incongruities and questions. You could analyze publication techniques: how fonts grew and diminished in popularity, how page-layout worked, how photography itself changed (regrettably, I didn’t think to pinpoint the year of the first color photograph in the Microcosm until it was too late). Or you could choose a theme like Student Protests at Dickinson, piecing together a story involving tense student-faculty relations, marches on the U.S. Army War College, the J. P. Stevens Textile Company, and a guillotine erected in the quads. Just one page alone can tell you so much. Take, for instance, the two-page spread dedicated to the September 11th attacks: at first I wondered why there were so few pictures, until I considered that every student’s eyes were glued to the television screen. And every picture was so carefully chosen, showing all sides of the tragedy as it occurred at Dickinson. Even the background image is not merely filler, but rather a photograph of the enormous flag erected by library workers along High Street. The depth of emotion in these pages is moving.

Another way to look at this project is through the eyes of a prospective student, or someone who’s interested in learning what Dickinson is about. I’ve chosen some of our best moments, but also some of our worst, but I know, if you search, that you’ll find an institution devoted to overcoming the challenges of the world—and the challenges of who we used to be—while carrying on our commitments to global engagement and a useful liberal arts education.

And finally, I encourage you to read this as a yearbook. Alumni, look back on your college days. Laugh, remember, and tell stories. Current students, admire your heritage, see how far we’ve come, and know we have a long way ahead of us. And please, do share your stories. I’ve provided as much context as I can for the pages I’ve incorporated (click the little red boxes on each page for annotations), but honestly, I might be wrong. Or I could be missing something, something important. Even so, I believe this project contains valuable insights into Student Life at Dickinson, moments and even people that wouldn’t show up in the “official histories” we expect from institutions. And with the pages I’ve chosen and your own comments and stories, we can weave together a greater story about Dickinson’s students, and from that microcosm, a picture of the greater world.

Very special thanks to

Professor Regina Sweeney, my advisor, who roped me into the Digital History independent study and supervised this whole project, start to finish.

Professor Emily Pawley, Cassidy Leighton, and other members of the Dickinsonia Project, who kept me motivated and on track.

Ryan Burke, who spent so much time helping me with the digital side of this project.

Alumni Karen Pflug-Felder '71, Dan Confer '02, and (now an alumni!) Aaron Brumbaugh '14; Professor Todd Wronski; Professor John Osborne; Director of Athletics Les Poolman; and Dickinson archivists Jim Gerencser '93, Malinda Triller, and Don Sailer '08 for all their help with my research.

Add new comment