Media

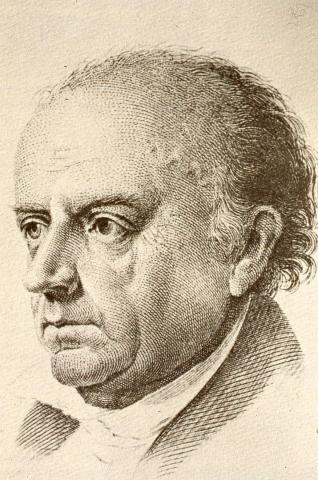

Joseph Priestley’s

Joseph Priestley’s

Text

“I have lived too long in the political world not to be well aware, that innovation, is not always reformation. But neither in the world of Politics, or the world of Science, can there be Reformation without it”, Thomas C. Cooper remarked to the students and faculty of Dickinson in his famous Introductory Lecture on Chemistry in August, 1811, soon after he was appointed a professor. Viewed against his unique background, such remark reveals the trace of resignation as well as determination at this moment of life.

Known as one of the ablest men of his time, a political-economist, jurist, educator, and scientific researcher, Cooper served as Professor of Chemistry and Natural Philosophy at Dickinson College from 1811 to 1815. With the help of the Priestley apparatus he obtained for the College, Cooper attracted many students to Dickinson’s experimental chemistry, and the scientific department at the College soon achieved national prominence. Despite his fame, he was constantly opposed. An outspoken supporter of the French Revolution and a religious Dissenter, he had fled, like his friend Joseph Priestley from Britain to America in 1794 under political persecution. However, in the “land of freedom”, he again ran into controversy. He clashed with members of the Federalist Party, who admired the British Parliamentary system and feared French style revolution. On the other hand, his revolutionary views endeared him to Democratic Republicans like Thomas Jefferson. In his protest against the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1799, he was imprisoned by the Federalists for several months, but was appointed a judge when Jefferson became President in 1800. When Cooper received the job from Dickinson College, he had just been forced out of his career as a judge. Casting himself as a man tired of the political-legal world, he wished to be eventually accepted by the academic sphere. However, despite his great contribution to the experimental sciences, the study of chemistry, and the prestige of the College as a whole, his appointment was terminated after four years, under fierce opposition from his colleagues to his religious opinions. Cooper was again excluded and expelled, marching alone in his unswerving quest for the “innovated”, the premise for the “reformation” he referred to in his talk.

The “reformation” for Cooper meant many things, from the improvement in mineralogical terminology he was pursuing, to the freedom from political tyranny he was constantly agitating for, or the state-based individual economy he believed in, which made him one of the earliest sessionists in America. All these thoughts and conducts, mostly viewed as radical by his time, made him a lonely man both respected and condemned.

Source: Thomas Cooper’s Letter to Nassau W. Senior, Columbia, South Carolina, April 1, 1835.