Media

Friday

Student marchers pass through downtown Carlisle.

Friday 3

One of the speakers addresses the crowd.

Friday 5

MPs faced the protesters outside of the War college, stretching across the road to prevent the students from entering the War College.

Friday 6

Students agreed to break into smaller groups to discuss the war with the MPs, who took off their helmets and listened to the concerns of the protesters.

Friday 7

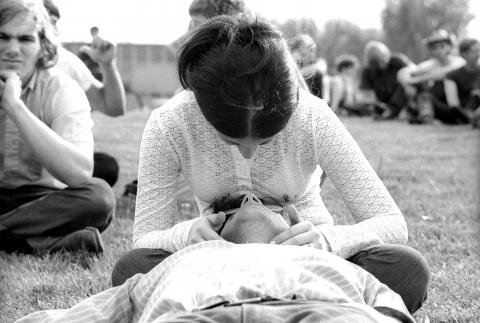

Students enjoy the warm weather on the field near the War College after the march concludes.

Friday 8

Carlisle children watch as the marchers pass them on High Street.

Friday 9

The marchers listened to speeches made by notable Peace movement figures and student leaders from the college. Despite high levels of enthusiasm, no speaker moved the crowd.

Text

Energy was high as students prepared for the culmination of their anti-war efforts. A sunny, 60-degree day provided a perfect background for the march on the War College. “The day, up until the march, was a slow build up of tensions,” wrote one student. While some worried about whether the event would turn into the next Kent State, some protesters were undecided about whether they would march at all. “Many saw it not just as a condemnation of our nation’s policy in Southeast Asia, but as a support of the radicals on campus,” one student explained.

Despite some last minute indecision, a crowd between 1200 and 2000 people, including Dickinson students, professors, students from nearby colleges, and even a few townspeople gathered on Morgan Field to prepare. After the Dickinsonian had reported that the War College had received a largely supply of tear gas, the protesters were drilled on non-violent responses. “Great emphasis was placed on what the marchers could do and what they could not do,” remembers one protester. These rules were enforced by more than 200 student Marshalls, which included the Skull and Key, a typically conservative organization. Professor Dondero patrolled the route, offering direction to the Marshals and marchers. Poole recalls the pressure of being a marshal: “We were paranoid about the town… all being college kids and all, we figured this college town was against us.” Poole even recalls seeing a man with a rifle on the roof of one of the downtown buildings, quickly notifying the police.

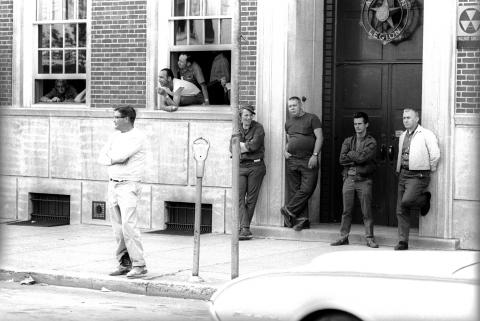

The Veterans of Foreign Wars watch from their building as the marchers pass.

Following the same course as the earlier march on the War College in November, the students began walking to the War College in rows of six, arms locked together. Shouting slogans like “Peace Now!” and “Rich Man’s War, Poor Man’s Fight,” the crowd proceeded past town residents and the Carlisle police. Students wrote about both positive and negative reactions from the townspeople. While the Dickinsonian reported that “reactions of the people of Carlisle to the march were mostly favorable,” others noted more conservative residents shouting obscenities at the students. The police maintained a heavy presence on the route throughout the march. “Corporal Jack Woodard of the Carlisle Police said that there was no resentment on the part of police to students. The expressions on some of their faces seemed to indicate otherwise,” wrote one student.

Professor Bullard remembered hostile confrontations between the townspeople, many of whom “thought it was disloyal, was not serving the country’s needs and was creating disunity where unity was necessary.” He recalled the owner of Cole’s Bicycle Shop standing with a rifle at the door of his store, and several townspeople holding pictures of soldiers up to the protesters. Bounds remembered the opposition as well, but also recalled “surprisingly positive kind of reactions, from some people. Gave the V sign and kind of cheered us on.”

Guido remembers making the choice with some of his brothers to walk parallel to the marching crowd to avoid getting “wrapped up into the crowd mentality.” Guido found the “party atmosphere” offensive, emphasizing that for him and his friends, the march “wasn’t an excuse to pick up chicks.” He met up with the marchers as they entered the intramural fields, gathering for the scheduled events just past the War College gates. Speakers included Professor Dondero, Neil Thomas from the ACLU, Professor William Davidson of Haverford College and Paul Krassner of the Yippie movement. One student remembers that Krassner “spoke in anecdotes, satirizing Nixon, rednecks, liberals, the movement, and just about everything else.” Despite the anticipation, no speaker moved the crowd, whose energy waned as the march ended. Students that did not intend to commit civil disobedience packed up their materials and marched peacefully past the gates back to the Dickinson campus.

Over a hundred students crossed the street to the War College and sat down on the road, blocking the entrance to the gates. “They believed, however, that the mere symbolic action of walking past the War College was not enough; they desired more direct action, confrontation if necessary,” explained one student. Many were worried that they would face another Kent State, while others were merely concerned with the legal consequences -- up to a year in prison and large fines. However, even when met with the MPs, there was no move to arrest the students.

The more radical students who wished to commit civil disobedience broke away from the march and sat in rows on the drive of the War College, facing a line of MPs.

Lieutenant Colonel Finkelstein remembered his reluctance to engage with the students at first. “I didn’t want to talk to them while they were in the streets, as far as I was concerned, I didn’t want to talk to lawbreakers,” he recalls arguing. Eventually, the War College representatives offered to come back to Dickinson to discuss the issues; the students refused but accepted their second offer to break into smaller groups and discuss the issues at the War College. Finkelstein said “the conversations we had with the marchers were the usual ones, you know. ‘Why do you kill babies every night? How many babies did you kill last week?” Student protesters saw the interaction as more productive: “Constructive dialogue followed which involved some students for almost three hours. Again, something which might have resulted in unfortunate consequences became a constructive learning experience,” wrote one student of the exchange.

The separate actions of the radicals and the moderates emphasized the ideological divide that remained even to the last day of the protests. “Monday began with different factions, radical and conservative alike, trying to use the movement to their own advantage, but by the march Friday afternoon everyone was working with one another. Disregarding purpose or ideals for the moment, it proved interesting to observe so many people unified in just the idea of strike,” wrote one student. As both groups were united on campus, most felt that although their protest did not have one single meaning, it was not meaningless.