Media

Thursday

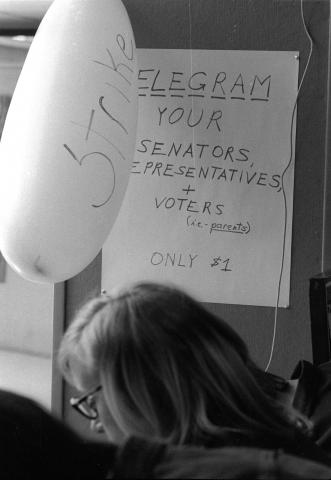

Tables in the student union asked Dickinson students to send telegrams to their representatives, parents, and alumni to promote the anti-war movement.

Letter to Faculty

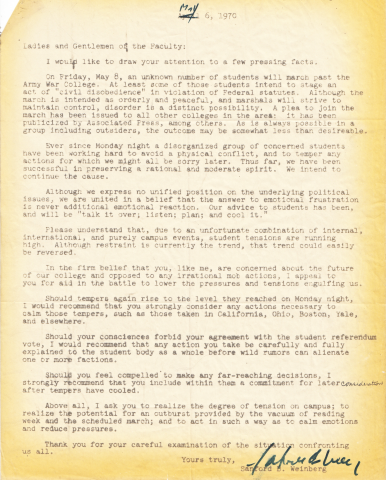

"Above all, I ask you to realize the degree of tension on campus; to realize the potential for an outburst provided by the vacuum of reading week and the scheduled march; and to act in such a way as to calm emotions and reduce pressures," wrote student Sanford B. Weinberg to the faculty in hopes of securing academic amnesty for striking students.

Faculty Resolution

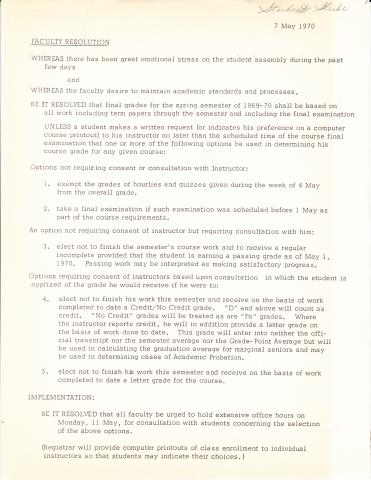

After a lengthy faculty meeting, this resolution was published so as to alleviate academic burdens for students participating in the protest activities.

Text

Early Thursday morning, 41 students chosen for their rhetorical abilities and geographical diversity left for Washington D.C. on a Dickinson bus to lobby their congressmen. While many felt that this was a valuable educational opportunity, others cited “the overabundance of legislative assistants and secretaries” as a frustrating exercise in bureaucracy. In the afternoon, the group met with anti-war Senators to discuss the movement on college campuses. While most returned glad of the experience, many also expressed doubts as to the success of the strategy.

Back on campus, an 11 am meeting of the Policy and Academic Standards Committee of the Faculty decided the academic fate of the striking students. This step was essential to the strike the next day because many students who wished to participate felt that their academic obligations took first priority and were discouraged from expressing their moral or political views. While some hoped that this meeting could have been earlier in the week, “most were reasonable sure that the faculty would go along with the strike,” explains one student. Students spoke to the faculty in this meeting, explaining that students “were finding it absolutely impossible to go back to the rooms and to study in the face of what they had seen happen to their fellow students at Kent State.”

After much debate, the committee devised a joint resolution that offered students several choices for completing the last week of classes. Dean Hawkins explained the five options to a meeting of students. Firstly, they could excuse the missed quiz grades from the past few days of strike but complete the final exam as scheduled; second, the students could take the final exam earlier; thirdly, with consultation of the instructor, a student could receive an incomplete grade and submit passing work later; fourthly, with consent of the instructor, choose not to finish the work and receive a credit/no credit grade; or lastly, with consent of the instructor, chose not to finish the work and receive the letter grade on the basis of work completed up to the point of the strike. For many students, the last option was especially attractive. Professors were encouraged to hold longer office hours on Monday so that striking students would have the opportunity to consult and receive consent for options 3 through 5.

The decision to pass striking students had serious implications. The students at Dickinson were only able to defer from the draft so long as they were enrolled in the college, and a failing grade therefore had much stronger consequences than a lowered GPA. Bullard recalls one case in which he passed a failing student: “I had to swallow hard and say, ‘I’m gong to pass this student with a C’ because I simply wanted the student to have the option of going into the military or not as long as possible.” The decision to pass the striking students was emblematic of the supportive attitude of the faculty as a whole, and especially the support of President Rubendall. While most of the faculty leaned left politically, few were truly radical and some had even witnessed firsthand the potential destructiveness of student protest at other universities. Rubendall was a “voice of moderation,” Poole remembers, but “he treated us respectfully and gave every impression that he respected our opinions. And that’s why nothing happened like Kent State.”

Not only did the faculty resolution on academic amnesty relieve tensions between the institution and the students, but it also had the unintentional effect of changing the narrative of the strike for some participants. Some students even saw this as a breakdown point: “Students felt the strike to be directed against the ‘Establishment,’ (a nebulous organization at best) and equated the College with the ‘Establishment.’ That the College could not possibly be called a part of the ‘Establishment’ is obvious from the actions of teachers and administrators during the crisis… However, when this resolution was passed, students felt they had defeated the College, to them the symbol of the ‘Establishment,’” a student explained. Once the college had agreed to the student demands, some factions saw this success as the end of their mission. It is unclear how many students fell into this category, however, and it appears that the majority of protesters remained committed to the Friday march.

More cynical students wrote of the abuse of the faculty resolution by students who merely hoped to get the best grades possible without taking finals. “Personal considerations are replacing national ones, unless, of course, national considerations were never the major motivation,” questioned one student. Poole agrees, admitting “I won’t say there weren’t some of us that got wrapped up in it just to get out of exams.”

At 4 pm, the general assembly met once more and heard announcements from the students who had gone to Washington D.C., as well as from SDS and the marchers who intended to commit civil disobedience. “The Thursday edition of the nightly meeting was for a change short, calm and uninspiring,” recalled one student. A proposal that the campus workers be allowed to join the strike was approved. As the day ended, students excitedly prepared for the march the next day.

Across town, the War College had been notified and had begun preparations as well. Lieutenant Colonel and War College student Zane Finkelstein recalled how he and his peers set out to “make it so we all could live together when it was over.” Interestingly, Finkelstein didn’t identify much with the National Guard in Kent State, noting that joining the National Guard was just another way to defer the draft, just like college. To prepare for the march, the War College students received brochures and sent for Military Policeman from Fort Meade. “We brought the MP company here [because] what people don’t understand is that our wives and children were in there. And people say we’re going to come trash the War College. Well, we weren’t about to let that happen.” While Finkelstein acknowledged the right of the students to assemble and protest, and even agrees that the issues of contention are “debatable,” he asserted that war policy should be made in democratic institutions of government, rather than street demonstrations. When asked about the SDS, he admitted the group “is not my favorite organization, but I got shot at so it could exist... it’s an important part of democracy, and I like people who take crazy views. I just wish they’d take crazy views in areas that weren’t my responsibility.”