Media

Wednesday

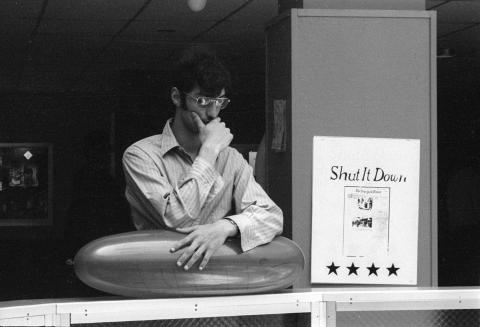

A student stands by the circular staircase in the student union by a poster calling for a strike.

Letters 4

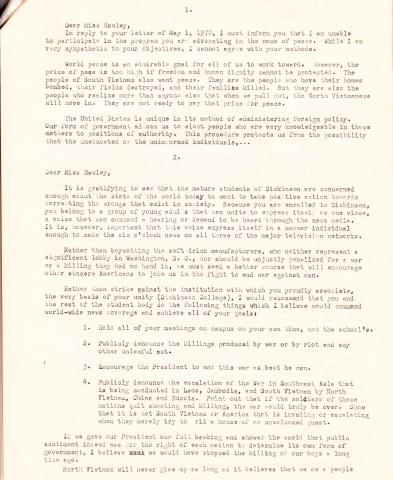

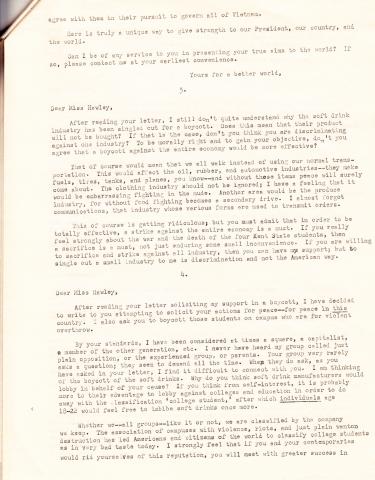

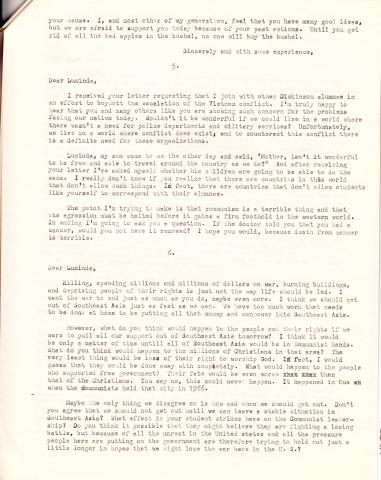

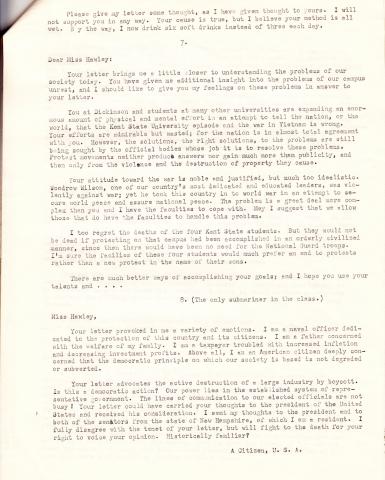

The letters above are a response from Naval Postgraduate School students after their professor, Dickinson Alumni Barbara Gabel, received a letter from a Dickinson Student asking her to participate in their boycott of soft drinks.

Text

On Wednesday, unified action began in earnest. With the collapse of the coalition narrowly averted the night before, Wednesday saw several developments. The anti-war effort was centered in the student union building. While the main student assemblies took place in the social hall, the entire building was alive with activity as various factions planned their own actions. “There were many informal and formal discussions being held in the side rooms of the Union. These discussions helped to solve many organizational problems involved and also to formulate and ‘hash out’ new ideas to bring before the assemblies,” wrote one student. Booths in the lobby were used to attract additional support for activities as well.

The design of the movement facilitated both separate campaigns representing a variety of viewpoints while also maintaining a united front in the student assemblies. For example, the letter writing campaign began in full force – an effort that by the end of the crisis produced more than 1000 letters to alumni. The students received a variety of letters back, some of which offered support and others condemnation. Alumna Barbara Bennett Gabel, a professor at the Naval Postgraduate School, had her considerably more conservative students write letters back to the protesters. "If we gave our president our full back and showed the world that public sentiment indeed was for the right of each nation to determine its own form of government, I believe we would have stopped the killing of our boys a long time ago," wrote one, expressing his support for Nixon's policies. "The association of campuses with violence, riots, and just plain wanton destruction has led Americans and citizens of the world to classify college students as in very bad taste today," responded another.

In addition, Alpha Chi Rho fraternity began a hunger strike in hopes of influencing a former fraternity member and influential Republican Senator Scott to change his position on the war. Guido recalls living on juice and crackers: “I lost a ton, I went home and I could see my ribs… my mother cried when she saw me.” His fraternity brother Bill Poole however admits that he can’t remember any real strike at all: “I can’t imagine that group of bozos doing anything like that. If we did a hunger strike it must have been that we were boycotting the dining hall, because I’m sure we didn’t go hungry.” Whatever the level of participation, the strike attracted the attention of local and even national media – Guido remembers an Associated Press reporter interviewing Alpha Chi Rho brothers.

This diverse array of activities lent the movement a new air of productivity: “The Holland Union was now analogous to a field headquarters of an advancing army. Indeed it was, the Dickinson College student body was on the move!” wrote one student.

Yet while much of the excited energy on campus was channeled into productive activities, others students remained outraged. “The atmosphere on campus was extremely tense and explosive,” wrote one student; another remembered “the high emotions and tension that flowed so anxiously during the strike.” At the afternoon teach-in, SDS leader Tony Marcson read a statement by Woodard, officially withdrawing the support of the Afro-American Society. Citing the incident of the night before, Woodard denounced the protest as absurd,. “It’s ridiculous to plead for the end to white supremacy in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos, to a white supremacy audience,” Woodard wrote. He added that “force was the only weapon the white supremacist understood,” recounts one student. Some students saw this added layer of discussion as a distraction: “The Black population of Dickinson tried to turn the aggression into racism by calling it a war of white supremacy,” wrote one student critically. Others expressed respect for Woodard and supported his objections; however, the debate on race was largely lost in the madness of the days to follow.

Later that day, a record-breaking 1,300 students cast ballots in the referendum, marking the largest turnout for a student vote in college history, with 91% of the student body participating. The students approved a measure to strike indefinitely (1043-269), voted down a measure for a total shutdown of the college (548-745), approved a measure that gave students who desire to do work the right to do so (1085-225), and voted to maintain ROTC on campus (757-530).

These votes are revealing. Some students remember the high turnout somewhat cynically, suggesting that perhaps even apolitical students showed up in hopes of getting out of exams. But despite the push for real action, the student body was against shutting down the school, voting to allow other students to complete academic work, and even to maintain ROTC. “What the hell were we going to do? We all lived there, we didn’t want to go home,” explained Poole. Poole also attributes the moderating influences on the background of the strikers, emphasizing: “We were a very polite, middle class group of radicals. We wanted our voices heard, but we didn’t want to disrupt anybody else’s life.”

In the late evening, the last student assembly meeting of the day met and announced that a permit had been obtained for Friday’s march, and that those who wished to commit civil disobedience would be separated from the majority of students were granted permission from the larger group to do so. Alpha Chi Rho encouraged more students to join their hunger strike and announced that Dining Services would reimburse students for missed meals to add to revenue for the strike.

Nationally, as many as 900 other campuses across the country had shut down or protested the Kent State shootings that week. Dickinson’s movement was bolstered by the actions of its peers. These efforts were largely coordinated out of Brandeis University. That night, a student from Bucknell University came to encourage students to boycott soda in hopes that pressuring the soft drink industry would earn the peace movement a powerful economic ally.

As a busy day ended, many camps began to grow more confident that the political will of the student protesters could be turned into something meaningful.