Media

Monday 2

As news of Kent State spread across campus, students gathered outside of the student union to figure out what their next step should be. The emotional crowd included a diverse range of class years and social groups.

Monday 5

Students await the faculty decision on ROTC on the steps of Old West on the night of Kent State.

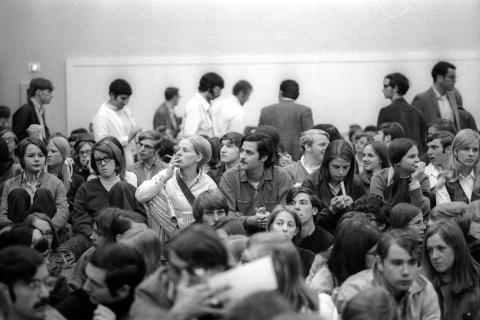

Monday 6

Students listen to the student speakers as they discuss the possibility of a strike in a chaotic meeting Monday night.

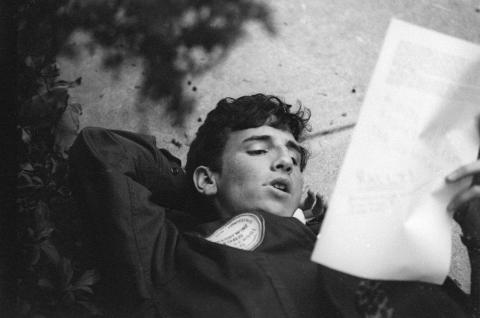

Monday 3

A student reads a flyer calling for a strike as he waits outside the student union with other protesters on Monday evening.

Monday 4

Students listen to the student speakers as they discuss the possibility of a strike in a chaotic meeting Monday night.

Text

One student recalled hearing about Kent State on the evening news, crying in front of the TV in his fraternity house; others cited the power of the gossip mill reaching every corner of campus; several other students pointed to messages sent over teletype. However the news of the shooting of four students at Kent State University first reached Dickinson, it sent shockwaves through the student body: “It hit the Dickinson Campus as nothing I have seen in the two years I have been here,” remembered one student.

In the months leading up to Kent State, it appeared the anti-war movement at Dickinson was on the decline. Political sentiment came in waves. Even moderates marched through Carlisle on Vietnam Moratorium Day in October 1969 but ranks thinned as winter froze over and the draft policy became less immediately threatening. While the Dickinson student body remained mostly liberal, it took the Kent State shootings to bring back the charged atmosphere of the early anti-Vietnam movement. For the students who had allowed their political will to grow dormant, the events in Ohio were a call to action. The very public deaths of “people like us” were a reminder of their own vulnerability. “With Monday’s news of Kent State, [their] desperation became acute; and there was not a place to channel this frustration,” wrote one student.

While the Student Senate President Dave Plymyer promised a student assembly meeting as early as Tuesday, the adrenaline-fueled students wanted action – now. And so in search of some outlet for their renewed energy, the growing bulk of moderate liberals turned to the Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS. SDS was known as the “fringe element” on campus, an ultra-leftwing group originating at the University of Michigan that represented the most radical of anti-war positions. Ideologically, both moderates and radicals were against the war, but while the SDS painted the conflict abroad as “economic exploitation with the American businesses enriching themselves at the expense of the workers and students,” the moderate liberals cited less systemic grievances and pointed to correcting specific injustices. Moreover, while the moderate liberals’ desire for protest waned as issues came and went, the radicals “would protest anything. And always, and all the time.” And while the moderates planned marches, strikes and boycotts, the radicals advocated civil disobedience and even violence. “There weren’t many people in Dickinson who had any interest in violent protests,” remembered alumni Bill Poole, leaving the truly radical fringe in the minority. But while both groups recognized their incompatibility, the mainstream group found no alternative outlet for their fevered passions and so joined the SDS in a rally scheduled for 8 pm.

As the moderates joined them, some radical students resented the apparent fad for protest: “The crisis at Dickinson College was that a majority of Dickinson students were not aware of certain conditions and governmental policies which existed in our country long before May 1970. It took the killing of four white middle class Kent State students by National Guardsmen and the escalation of the Viet Nam War to wake them up to certain conditions,” wrote an annoyed student.

Regardless of these sentiments, over 800 students showed up for the planned rally outside of the student union building. Inside, the last faculty meeting of the year debated whether to not to keep ROTC on campus. As students waited, a petition for an emergency meeting of the general student assembly to be held that night was passed around the crowd.

For the faculty, the debate over ROTC was complicated. Music Professor Truman Bullard recalled that some liberal faculty “felt banishing ROTC was not a good idea for keeping a dialogue going with our national defense establishment.” Others saw it as a problematic symbol: “ROTC is an unnecessary extension of military on campus; it institutionalizes death and is a convenient way for avoiding the draft,” argued Professor Dondero of the Political Science Department. At 10 pm, the faculty announced by a vote of 74-41 that they would not abolish ROTC; by a vote of 64-49, however, they announced that they would eliminate academic credit for the program. The compromise further infuriated the protesters, who had at this point gathered enough signatures to authorize an emergency meeting for 11 pm.

The emergency meeting was chaotic, unruly, and heated. As Plymyer attempted to lead the body towards organized action, the thousand-plus students retreated into several ideological camps. The ideological conflicts between the moderates and the fringe soon became obvious: “the radicals, grouped at the front of the assembly, excitedly shouting out slogans and generally trying to take over the meeting. They succeed in shouting down several speakers and generally played on peoples emotions by making wild speeches and resolutions,” remembered one student. After much debate, Plymyer made a motion to strike until Wednesday, when the strike would be re-evaluated; the vast majority of students affirmed this motion. In addition, it was resolved that Plymyer would compose a letter to the Adjutant General of the Ohio National Guard to express their concerns about the violence at Kent State, and that a delegation of students from as many congressional districts as possible would go to Washington D.C. to speak with their representatives.

Yet for the radicals, emotions ran too high for this restrained response. Barry Lynn stood among his peers, shouting above the chaos: “Enough talk. It’s time to take action.” Whether his words were an intended directive or misinterpreted, several hundred students found the proposal of a midnight march too attractive to pass up. Running back to their dorms for coats to brave the forty degree weather, their enthusiasm was dampened by reports that town residents were circling campus with shotguns in anticipation of student reaction. Thinking back on that night, Poole guesses that the chilly night and distance would have deterred the vast majority of moderate liberals anyway. But when a few hundred of the more radical students returned to the student union Building to begin the illegal march, a young female student ran to wake up President Rubendall. Former College President Bill Durden remembers hearing that Rubendall arrived in the Social Hall in his pajamas (a detail since debated). Whatever his attire, Rubendall insisted that it was much too dangerous to march illegally in the dark and assured the students he would get them a permit to march in the daytime within twenty four hours. “He was afraid for human life. He was afraid that at night people would not be able to see as well, either side or both sides, and that could lead to catastrophes, to deaths,” remembered Bullard, “It really was the finest moment in Rubendall’s presidency.”

Rubendall’s commanding presence and promises of future support appeased both the radical and moderate factions. “The radicals were tentatively satisfied, as they were on strike; and the moderate faction was relieved in that the illegal march had not taken place,” writes one student. The divided student body returned to their protest, many still energized by the events of the day and ready to protest in earnest.