Morphine: An Introduction | Discovery and Synthesis of Morphine | Addiction and Opiate Receptors | | History Affects Morphine: The Hypodermic Needle | History Affects Morphine II: Cultural Antipathy and Anti-Narcotics Law| References

References

(1892). History of Opium, Opium Eating and Smoking. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 21, 329-332.

Berridge, V., & Edwards, G. (1987). Opium and the People. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Blakemore, P., & White, J. (2002). Morphine, the Proteus of Organic Molecules. Chemical Communications, 1159-1168.

Booth, M. (1999). Opium: A History. New York, New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Brownstein, M. (1993). A Brief History of Opiates, Opiod Peptides, and Opiod Receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 90(12), 5391-5393.

Courtwright, D. (1982). Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Freemantle, M. (2005, June 5). Top Pharmaceuticals: Morphine. Retrieved Apr. 28, 2008, from http://pubs.acs.org/cen/coverstory/83/8325/8325morphine.html

Goldberg, R. (2005). Drugs Across the Spectrum (with InfoTrac ). New York: Brooks Cole.

Hamilton, G., & Baskett, T. (2000). History of Anesthesia. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 47(4), 367-374.

Herbert, R., Venter, H., & Pos, S. (2000). Do Mammals Make Their Own Morphine?. Natural Product Reports, 17, 317-322.

Hodgson, B. (2001). In the Arms of Morpheus: The Tragic History of Morphine, Laudanum and Patent Medicines. Toronto: Firefly Books.

Karch, S. (2005). A Brief History of Cocaine, Second Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Le Couteur, P., & Burreson, J. (2003). Napoleon’s Buttons. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

“Opium Throughout History.” (n.d.). Retrieved Apr. 15, 2008, from http://www.pbs.org/

wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/heroin/etc/history.html

Richards, J. (2002). Opium and the British Empire: The Opium Commission of 1895. Modern Asian Studies, 36(2), 375-420.

Schiff Jr. , P. (2002). Opium and Its Alkaloids. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 66, 186-194.

Schwarz, S., & Huxtable, R. (2001). The Isolation of Morphine. Molecular interventions, 1(4), 189-191.

Shughart, W. (1997). Taxing Choice: The Predatory Politics of Fiscal Discrimination. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Stimmel, B., & Shaffer, H. (1984). The Addictive Behavior. New York: Routledge. Waldron, K. (2007). The Chemistry of Everything. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

[Read more →]

Morphine: An Introduction | Discovery and Synthesis of Morphine | Addiction and Opiate Receptors | Morphine Affects History: Modern Pharmacology | History Affects Morphine: The Hypodermic Needle | History Affects Morphine II: Cultural Antipathy and Anti-Narcotics Law| References

-

During the 19th century morphine – like many other narcotics of the day – was not regulated by federal law

-

The actual impetus for the criminalization of drugs lay in the transformation of drug users into “moral reprobates” (Watters)

-

By the end of that century, the view of drug use went from that of illness – as seen with Civil War soldiers – to that of a “manifestation of moral weakness;” such a negative view was linked to growing animosity toward immigrants from East Asia, as drugs – especially opium – became indicative of a foreign adulteration of “pure” American culture (Renner)

-

It may have also linked to residual Puritan values and the Third Great Awakening; William Shughart states that the “federal antinarcotics crusade […] is justifiably seen as a component of the progressive-prohibitionist campaign that originated with the religious precepts of the Puritan colonists”

-

In response to these undercurrents, then, many states adopted anti-narcotics laws in the late 1890s, and the federal government followed suit, passing both the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914

-

The Pure Food and Drug Act required contents to appear on the label of many products, and as a result, the amount of morphine and cocaine in pharmaceuticals was not only reduced, but the demand for and use of morphine, opium, and heroin dropped drastically

-

As for the Harrison Act, which marked the “first salvo in the war on drugs” (Renner), it put intense pressure via tax legislation on the many public morphine maintenance clinics, at which addicts could receive their drug from physicians

[Read more →]

Morphine: An Introduction | Discovery and Synthesis of Morphine | Addiction and Opiate Receptors | Morphine Affects History: Modern Pharmacology | History Affects Morphine: The Hypodermic Needle | History Affects Morphine II: Cultural Antipathy and Anti-Narcotics Law| References

“Ah! Pierce me one hundred times with your needle fine

And I will thank you one hundred times, Saint Morphine,

You who Aesculapus has made a God.”

– Jules Verne

(Poem taken from In the Arms of Morpheus by Barbara Hodgson)

-

Despite its impact on the science of pharmacology, morphine had limited medical impact until the invention of the hypodermic needle in the 1840s/1850s

-

A number of individuals are associated with the invention of the hypodermic needle, but among them, Alexander Wood, a Scottish physician, is perhaps the most prominent

-

Wood used morphine in conjunction with his newly invented needle to treat a patient with neuralgia, otherwise known as a sharp pain in the nerves; unfortunately, Wood also used his device on both he and his wife, and both became addicted. In fact, Wood’s wife became the first woman to die of a narcotic drug overdose

-

In light of this, however, Wood found that upon injection, morphine’s results were both immediate and much more powerful, certainly a success; such success led to a rise in the medical use of morphine, especially in the realm of surgery and anesthesia

-

Unfortunately, though, morphine administered through hypodermic needle was not thought to be addictive, and thus it further proliferated the drug, increasing use and addiction

-

Interestingly, it is worth noting that shortly after the time of the hypodermic needle’s inception, there began a debate over whether the effects of morphine post-injection were localized or not; and while many believe the effects to be non-localized – hence the name hypodermic – the debate actually continues to this day

Historical perspective: old syringes

(http://www.aaic.net.au/PDF/1999485.pdf)

[Read more →]

Morphine: An Introduction | Discovery and Synthesis of Morphine | Addiction and Opiate Receptors | Morphine Affects History: Modern Pharmacology | History Affects Morphine: The Hypodermic Needle | History Affects Morphine II: Cultural Antipathy and Anti-Narcotics Law| References

– Friedrich Sertürner experimenting in his lab

http://www.pharmacy.wsu.edu/History/images/picture23.jpg –

-

The isolation of morphine in its pure form was the result of years of research and testing, occurring most prominently between the years 1803 and 1817. During this time, three men – Derosne, Seguin, and Sertürner – all had some form of success, but it is the latter that is today best remembered.

-

Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Sertürner, a German pharmacist born in Neuhaus in what is today Germany, effectively isolated pure morphine from opium in the year 1817.

-

To do this, Sertürner extracted opium with hot water, precipitating the morphine with ammonia (Huxtable and Schwarz 2001). This process yielded water-insoluble colorless crystals.

-

To prove that this isolate had the same effects as the opium from which it came, Sertürner ran experimental tests on both he himself and three young boys, a method indicative of the times. And while Sertürner’s experiment indeed proved the shared properties of his crystals and opium, it was nearly disastrous, bringing forth “severe narcosis,” “pain,” and “exhaustion” in all four test subjects.

-

Because Sertürner likewise experienced a dream-like state while under the influence, he named the compound “Morphium,” after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams (as named by Ovid, a Roman). Interestingly, the name we know today – morphine – came not from Sertürner but from Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, who changed the name in his German-to-French translation, much to Sertürner’s chagrin.

-

It is important to note that although Sertürner isolated morphine, it took until 1925 for someone – one Sir Robert Robinson – to deduce the empirical formula, and it took until 1952 for one Marshall D. Gates, Jr. to synthesize morphine in a laboratory.

[Read more →]

Morphine: An Introduction | Discovery and Synthesis of Morphine | Addiction and Opiate Receptors | Morphine Affects History: Modern Pharmacology | History Affects Morphine: The Hypodermic Needle | History Affects Morphine II: Cultural Antipathy and Anti-Narcotics Law| References

(An lanced opium poppy; morphine is its active ingredient –

http://www.rsc.org/ej/CC/2002/b111551k/b111551k-f1.gif)

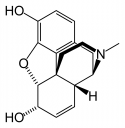

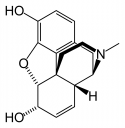

Morphine is an alkaloid molecule, a term given to “natural occurring nitrogen-containing bases found mainly in plants” (NB 249). It is one of twenty-four such alkaloids found within the resin of the opium poppy plant – Papaver somniferum – and it usually comprises 10% of all opium extract.

Designated with the chemical formula C17H19NO3, morphine exists mainly as a “bitter, white crystalline compound” (C&E News), one that is water-insoluble. It has appeared and continues to appear in a variety of other forms, however, including, but not limited to: pharmaceutical concoctions (i.e. Patent medicines), morphine acetate (salt), morphine hydrochloride (salt), and morphine sulfate (salt).

Because of these possible physical forms, morphine has been both ingested and injected throughout history, all in attempt to exploit its wonderful analgesic and euphoric effects – properties unfortunately linked to physiological addiction. It is these consequences of consumption that make morphine both an incredibly important and intriguing molecule to study. A double-edged sword in every way, morphine has been both a bane and boon to human existence.

Morphine’s Chemical Structure:

(http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/64/Morphine-2D-skeletal.png)

JMol Image:

[Read more →]